This guide is for the programmer who needs to use Python with a deep and precise understanding of its mechanics. It is not a beginner’s tutorial. It assumes you understand the concepts of loops, functions, and data structures. Instead of teaching you to code, it aims to build a correct and robust mental model of how Python works, from practical environment setup to the nuances of its object model, memory management, and concurrency. In short, it’s the resource I wish I had when I was piecing these ideas together on my own.

- If you just want a quick and easy reference: https://www.pythoncheatsheet.org/

- Python Docs (Language, Standard Lib, …): https://docs.python.org/3/

Table of Contents

-

The Pragmatic Setup

- The Execution Model: Interpreter, Bytecode, and the PVM

- Environment Management: The Necessity of Isolation

- Project Structure:

pyproject.tomland Modern Tooling - Workflow: Interactive Notebooks vs. Scripts

-

Language Fundamentals

- Syntax, Indentation, and Comments

- Core Data Types:

int,float,bool,str,None - Container Types: A Deep Dive

list: Mutable Dynamic Arraystuple: Immutable Sequencesdict: The Power of Hash Mapsset: Hashing for Uniqueness and Speed

- Hashability: The Key to Dictionaries and Sets

- Control Flow and Pythonic Idioms

- Conditionals and Loops

- Comprehensions: The Superior Alternative

-

Structuring Code

- Functions: Arguments, Scope, Decorators, and Type Hints

- Error Handling:

try,except,finally - Context Managers and the

withStatement - Modules and Imports: Namespaces in Practice

- Classes: Beyond the Basics (

__init__,__repr__, Inheritance,__slots__)

-

The Deep Dive: Python Internals

- The Object Model: Names, References, Identity, and Interning

id()vs.__hash__(): A Critical Distinction- Mutability, Immutability, and Function Arguments

- Memory Management: Reference Counting and the Cyclic Garbage Collector

- Iterables, Iterators, and Generators: The Protocol of Sequence

- Concurrency and Parallelism:

threading,asyncio, andmultiprocessing

The Pragmatic Setup

The Execution Model: Interpreter, Bytecode, and the PVM

When you run python my_script.py, the code is not executed line-by-line directly.

- Compilation to Bytecode: The source code is first compiled into a platform-independent representation called bytecode. This is a set of instructions for a stack-based virtual machine. This bytecode is cached in

.pycfiles inside a__pycache__directory to avoid recompilation of unchanged files. - Interpretation by the PVM: The Python Virtual Machine (PVM), the runtime engine of Python, then executes this bytecode.

This two-step process is faster than pure line-by-line interpretation but carries significant overhead compared to running native machine code. This overhead is why Python loops are slow.

Environment Management: The Necessity of Isolation

Never use your system’s global Python installation for development. Doing so will inevitably lead to dependency conflicts between projects. Every project must have its own isolated virtual environment.

A virtual environment is a self-contained directory tree that contains a specific Python installation and any number of additional packages. The modern, recommended tool for this is uv, which is significantly faster than the standard venv and pip.

Project Structure: pyproject.toml and Modern Tooling

Modern Python projects are defined by a pyproject.toml file at their root. This file centralizes project metadata, dependencies, and tool configurations (like linters and formatters).

The Recommended Modern Workflow (uv):

- Initialize Project:

uv init. This creates apyproject.tomland a virtual environment (.venv). - Activate Environment:

source .venv/bin/activate(Linux/macOS) or.venv\Scripts\activate.bat(Windows). - Initialize Project:

uv init - Add Dependencies:

uv add "requests<3"oruv add black --dev. This adds the package to your environment and updatespyproject.toml(which is better than therequirements.txtfile approach) - Sync Environment: If you pull changes, run

uv syncto install dependencies exactly as specified inpyproject.toml.

Workflow: Interactive Notebooks vs. Scripts

Jupyter Notebooks (.ipynb) are excellent for exploration and prototyping. However, they have significant drawbacks for reproducible work:

- Hidden State: The execution order of cells is arbitrary, making it easy to create a notebook that is not reproducible from top to bottom.

- Poor Version Control: The JSON format with embedded outputs makes

git diffs nearly unreadable.

Best Practice: Use notebooks for exploration. Once a piece of logic is solidified, refactor it into a version-controlled .py script or module.

Language Fundamentals

Syntax, Indentation, and Comments

Python uses indentation (conventionally 4 spaces) to denote code blocks, replacing the curly braces of other languages. This is a syntactic requirement.

# This is a single-line comment

def some_function():

x = 10 # Start of an indented block

if x > 5:

print("x is greater than 5") # A nested blockCore Data Types

int: Arbitrary-precision integer.float: 64-bit double-precision floating-point number (IEEE 754).bool:TrueorFalse. Subclasses ofint, whereTrue==1 andFalse==0.str: An immutable sequence of Unicode characters. CPython performs an optimization called string interning, where it reuses existing string objects for short, simple strings to save memory. This is whya = 'hi'; b = 'hi'; a is bcan beTrue.None: A singleton object of typeNoneTypeused to represent the absence of a value.

Container Types: A Deep Dive

list: Mutable Dynamic Arrays

A list is a mutable, ordered sequence of objects.

- Implementation: A CPython

listis a dynamic array of pointers to Python objects. - Performance:

append(x)is amortized O(1).insert(i, x)orpop(i)is O(n).x in my_listis O(n).my_list[i]is O(1).

tuple: Immutable Sequences

A tuple is an immutable, ordered sequence of objects.

- Use Cases: Data integrity (for collections that shouldn’t change), performance (slightly faster and smaller than lists), and as dictionary keys.

dict: The Power of Hash Maps

A dict is a mutable collection of key-value pairs, implemented as a hash map.

- Performance: Get/Set/Delete operations are average case O(1).

- Ordering: As of Python 3.7+, dictionaries preserve insertion order.

set: Hashing for Uniqueness and Speed

A set is a mutable, unordered collection of unique, hashable objects, also implemented with a hash table.

- Performance: Membership testing (

x in my_set) is O(1) on average, its primary advantage over lists. - Use Cases: Removing duplicates, fast membership testing, and set-theoretic operations (

union,intersection).

Hashability: The Key to Dictionaries and Sets

The performance of dict and set relies on their elements being hashable.

What does “hashable” mean?

An object is hashable if it has a hash value that never changes during its lifetime. This requires two things:

- The object has a

__hash__()method that returns an integer. - The object has an

__eq__()method for equality comparison. - The contract: If

a == bis true, thenhash(a) == hash(b)must also be true.

The hash value is used to quickly locate the “bucket” in the hash table where the object should be stored. __eq__ is then used to resolve collisions if multiple objects hash to the same bucket.

Which types are hashable?

- All built-in immutable types are hashable:

int,float,bool,str,tuple,None. - All built-in mutable types are not hashable:

list,dict,set. This is because their values (and thus their hash) could change, breaking the hash table’s invariants.

The Practical Trick: Making the Unhashable, Hashable

You cannot use a list as a dictionary key. But if you need to, you can often convert it to a tuple, which is hashable.

my_list = [1, 2, 'config_A']

my_dict = {}

# This will fail:

# my_dict[my_list] = "some_data" # TypeError: unhashable type: 'list'

# The solution: convert to a tuple

key = tuple(my_list)

my_dict[key] = "some_data" # This works perfectly

print(my_dict[(1, 2, 'config_A')]) # 'some_data'Control Flow and Pythonic Idioms

Conditionals and Loops

The syntax for if/elif/else, for, and while is standard. The for loop is a “for-each” loop. To get an index, use enumerate.

for i, item in enumerate(['a', 'b', 'c']):

print(f"Index {i}: {item}")Comprehensions: The Superior Alternative

Comprehensions are a concise, readable, and efficient way to create containers from iterables. They are almost always preferred over explicit for loops.

# List Comprehension

squares = [i * i for i in range(10) if i % 2 == 0]

# Dict Comprehension

square_dict = {i: i * i for i in range(5)}

# Set Comprehension

unique_squares = {i * i for i in [-1, 0, 1, 2]}Structuring Code

Functions: Arguments, Scope, Decorators, and Type Hints

Functions are first-class objects.

Mutable Default Arguments: The Classic Pitfall

Default arguments are evaluated once, when the function is defined. Never use a mutable object (like [] or {}) as a default argument.

# INCORRECT

def bad_append(item, my_list=[]):

my_list.append(item)

return my_list

print(bad_append(1))

print(bad_append(2))

print(bad_append(3))

# Output:

# [1]

# [1, 2]

# [1, 2, 3]

# CORRECT

def good_append(item, my_list=None):

if my_list is None:

my_list = []

my_list.append(item)

return my_list

print(good_append(1))

print(good_append(2))

print(good_append(3))

# Output:

# [1]

# [2]

# [3]*args and **kwargs: Flexible Arguments

*args collects any number of positional arguments into a tuple. **kwargs collects any number of keyword arguments into a dictionary.

def flexible_function(pos1, pos2, *args, **kwargs):

print(f"Positional: {pos1}, {pos2}")

print(f"Extra positional args: {args}")

print(f"Keyword args: {kwargs}")

flexible_function('a', 'b', 3, 4, key1='val1', key2='val2')

# Positional: a, b

# Extra positional args: (3, 4)

# Keyword args: {'key1': 'val1', 'key2': 'val2'}Decorators: Modifying Function Behavior

A decorator is a function that takes another function as input, adds some functionality, and returns another function. This is done without altering the source code of the original function.

import time

def timing_decorator(func):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

start_time = time.time()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end_time = time.time()

print(f"'{func.__name__}' took {end_time - start_time:.4f} seconds.")

return result

return wrapper

@timing_decorator

def slow_function(delay):

time.sleep(delay)

slow_function(1) # Output: 'slow_function' took 1.00XX seconds.Type Hints: For Clarity and Static Analysis

Python is dynamically typed, but you can add type hints for function signatures. These are not enforced at runtime but are invaluable for code readability and for static analysis tools like mypy.

def greet(name: str) -> str:

return f"Hello, {name}"Error Handling: try, except, finally

Exceptions are the standard way to handle errors. The try...except...else...finally block provides a robust structure for this.

try:

result = 1 / int(some_input)

except (ValueError, ZeroDivisionError) as e:

print(f"Invalid input: {e}")

finally:

print("Cleanup actions here.") # Always executedContext Managers and the with Statement

The with statement simplifies resource management (like files or locks) and ensures that cleanup code is always executed. Any object with __enter__() and __exit__() methods can be used as a context manager.

with open('file.txt', 'w') as f:

# f.close() is automatically called when the block is exited,

# even if an error occurs.

f.write('hello')Modules and Imports: Namespaces in Practice

Every .py file is a module. The import statement brings code from one module into another.

import my_module: Preferred. Creates a namespace (my_module.func()).from my_module import my_function: Use with caution to avoid name collisions.from my_module import *: Avoid. Pollutes the namespace.

Classes: Beyond the Basics (__init__, __repr__, Inheritance, __slots__)

“Dunder” (double underscore) methods define how objects behave with Python’s built-in operations.

__init__(self, ...): The constructor.__repr__(self): The “official” string representation. Should be unambiguous.__str__(self): The “informal” or user-friendly string representation. Called byprint().

Inheritance and Method Resolution Order (MRO)

Python supports multiple inheritance. It determines which method to call using the C3 linearization algorithm, which produces a predictable Method Resolution Order (MRO). Use super() to call methods from a parent class.

class Base:

def greet(self):

return "Base"

class Child(Base):

def greet(self):

# Call the parent's method and extend it

return f"Child, extending {super().greet()}"__slots__: Memory Optimization

By default, Python instances store their attributes in a __dict__, which is a memory-hungry dictionary. If you are creating thousands of instances of a class with a fixed set of attributes, you can use __slots__ to save significant memory.

class Point:

__slots__ = ('x', 'y') # No __dict__ will be created for instances

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

# p = Point(1, 2)

# p.z = 3 # This will raise an AttributeErrorThe Deep Dive: Python Internals

The Object Model: Names, References, Identity, and Interning

Python does not have variables in the C sense. It has names that are bound to objects.

x = [1, 2, 3]

This creates a list object in memory and binds the name x to it.

y = x

This creates a new name, y, and binds it to the exact same object. id(x) == id(y) will be True.

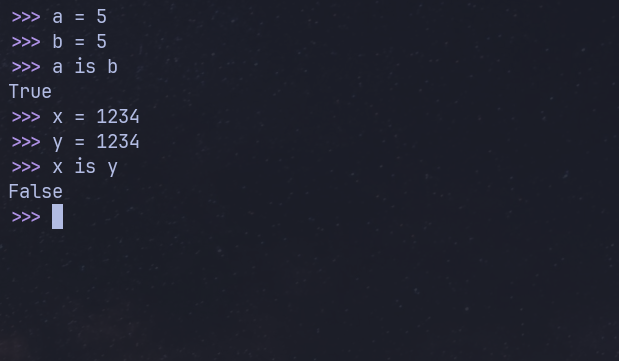

A common “gotcha”: CPython pre-allocates and caches small integers (from -5 to 256). For these numbers, a = 5; b = 5; a is b will be True. For larger numbers, it’s False. Never rely on this behavior. Use == for value equality and is for identity comparison.

is vs. == vs. hash(): Identity, Equality, and Hashing

This is a frequent point of confusion, yet understanding the distinction is fundamental to grasping Python’s object model. These three mechanisms answer three different but related questions:

is: Are these two names pointing to the exact same object in memory? (Identity)==: Do these two objects have the same value? (Equality)hash(): Where does this object go in a hash map? (Hashing)

Identity: is and id()

The id() function returns a unique integer for a given object during its lifetime. In CPython, this is the object’s memory address. The is operator is simply syntactic sugar for comparing the id() of two objects.

- Mechanism:

a is bis equivalent toid(a) == id(b). - Purpose: To check if two names refer to the very same instance.

a = [1, 2, 3]

b = a # b is another name for the same list object

c = [1, 2, 3] # c is a new, independent list object

print(f"id(a): {id(a)}, id(b): {id(b)}, id(c): {id(c)}")

# id(a): 4389443648, id(b): 4389443648, id(c): 4389443904 (Addresses will vary)

print(a is b) # True - a and b point to the exact same object.

print(a is c) # False - a and c are different objects in memory.Equality: == and __eq__()

The == operator checks for value equality. It doesn’t care if the objects are the same instance in memory; it only cares if their contents are considered equal.

- Mechanism:

a == bis syntactic sugar that callsa.__eq__(b). - Purpose: To check if two objects have the same value, as defined by the object’s class. For built-in types, this works as you’d expect. For custom classes, you can define what equality means by implementing the

__eq__method.

If a class does not implement __eq__, the default behavior is to fall back to an identity check (is).

# Continuing the previous example:

a = [1, 2, 3]

b = a

c = [1, 2, 3]

print(a == b) # True - They are the same object, so their values are equal.

print(a == c) # True - They are different objects, but their values are equal.Hashing: hash() and __hash__()

The hash() function is used for one specific purpose: to enable fast lookups in hash-based data structures like dict and set.

- Mechanism:

hash(obj)callsobj.__hash__(). This method must return an integer. - Purpose: To compute an integer that helps a hash map quickly locate the “bucket” where an object might be stored.

The Critical Relationship: The Hashability Contract

The three concepts are tied together by a fundamental rule required for dictionaries and sets to work correctly:

If

a == bis true, thenhash(a) == hash(b)must also be true.

Why? Imagine this contract was violated. You could create two keys, key1 and key2, that are equal in value (key1 == key2). If they had different hashes, the dictionary might store the value in one location for key1 but look in a completely different location when you try to retrieve it with key2, failing to find it. The __eq__ method is used as a fallback to resolve hash collisions (when two different objects have the same hash).

The inverse is not required: hash(a) == hash(b) does not imply a == b. This is a hash collision, and it’s a normal part of how hash maps work.

Summary Table

| Concept | Operator / Function | Mechanism | Answers the Question… |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity | is, id() | id(a) == id(b) | ”Are a and b the exact same object in memory?” |

| Equality | ==, __eq__() | a.__eq__(b) | ”Do a and b have the same value?” |

| Hashing | hash(), __hash__() | obj.__hash__() | ”What is a hash value for this object for dict/set use?” |

Mutability, Immutability, and Function Arguments

Python’s argument passing is “pass-by-assignment”. The function parameter becomes a new name for the object passed in.

- If you pass a mutable object (

list,dict), the function can modify the original object in-place. - If you pass an immutable object (

str,int,tuple), the function cannot change the original object.

Memory Management: Reference Counting and the Cyclic Garbage Collector

CPython’s primary memory management is reference counting. Every object has a counter of how many names refer to it. When this count drops to zero, its memory is immediately deallocated.

This system fails for reference cycles (e.g., a.b = b; b.a = a). To solve this, a secondary cyclic garbage collector periodically runs to find and clean up these unreachable cycles.

Iterables, Iterators, and Generators: The Protocol of Sequence

This is a core concept in Python.

- Iterable: An object that can be looped over. It is any object that has an

__iter__()method, which returns an iterator. Examples:list,str,dict. - Iterator: An object that represents a stream of data. It is any object that has a

__next__()method, which returns the next item or raisesStopIterationwhen exhausted. An iterator must also have an__iter__method that returns itself.

The for loop works by first calling iter() on the iterable to get an iterator, and then repeatedly calling next() on that iterator until StopIteration is caught.

Examples

# Iterable: list

nums = [1, 2, 3]

it = iter(nums) # get an iterator

print(next(it)) # 1

print(next(it)) # 2

print(next(it)) # 3

# next(it) # raises StopIteration

# Iterator: custom

class CountDown:

def __init__(self, start):

self.current = start

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

if self.current <= 0:

raise StopIteration

self.current -= 1

return self.current

cd = CountDown(3)

for x in cd:

print(x) # 2, 1, 0Generators

Generators are the easiest way to create iterators.

- Generator Function: A function that uses the

yieldkeyword. When called, it returns a generator object (an iterator). The function’s state is saved between calls tonext().

def my_range(stop):

n = 0

while n < stop:

yield n

n += 1

gen = my_range(3)

print(next(gen)) # 0

print(next(gen)) # 1

print(next(gen)) # 2

# next(gen) # raises StopIteration- Generator Expression: A concise, comprehension-like syntax for creating generators.

# This creates a generator object, it does not build a list in memory.

lazy_squares = (i*i for i in range(5))

for x in lazy_squares:

print(x) # 0, 1, 4, 9, 16The key benefit of generators is lazy evaluation. They produce values one at a time and on demand, making them extremely memory-efficient for working with large data streams.

Concurrency and Parallelism: threading, asyncio, and multiprocessing

First, the definitions:

- Concurrency: Managing multiple tasks at once. The tasks may be interleaved, but not necessarily running at the same instant.

- Parallelism: Executing multiple tasks at the exact same instant, requiring multiple CPU cores.

The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)

The GIL is a mutex that ensures only one thread can execute Python bytecode at a time within a single process. This simplifies CPython’s memory management but is a major bottleneck. All three concurrency models are designed around this limitation.

1. threading

- Mechanism: Uses real OS threads. The OS can switch between threads preemptively.

- The Catch: Due to the GIL, only one thread can run Python code at a time.

- Best For: I/O-bound tasks. When a thread waits for I/O (e.g., a network request), the GIL is released, allowing another thread to run. This creates the illusion of parallelism and improves throughput.

- Not For: CPU-bound tasks. It will be slower than a single-threaded approach due to thread management overhead.

2. multiprocessing

- Mechanism: Bypasses the GIL by creating separate OS processes. Each process has its own Python interpreter, memory, and its own GIL.

- The Catch: Processes are heavier than threads (more memory, slower to start). Communicating between processes (Inter-Process Communication or IPC) is more complex and slower than sharing memory in threads.

- Best For: CPU-bound tasks. This is the only way to achieve true parallelism for Python code on multi-core machines. Ideal for data processing, calculations, and simulations.

3. asyncio

- Mechanism: A single-threaded, single-process model using an event loop and cooperative multitasking.

- The Catch: Code must be written in a special, non-blocking style using

asyncandawait. Anawaitcall explicitly yields control back to the event loop, allowing it to run another task. If any task blocks withoutawait, the entire application freezes. - Best For: High-throughput I/O-bound tasks. Excellent for applications with thousands of network connections (e.g., web servers, database clients, APIs) because the overhead per task is extremely low.

Summary: Which One to Use?

| Feature | threading | multiprocessing | asyncio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best For | I/O-bound tasks (simpler use cases) | CPU-bound tasks | High-throughput I/O-bound tasks (networking) |

| Unit of Execution | Thread | Process | Task (managed by event loop) |

| Parallelism | No (Concurrency only, due to GIL) | Yes (True parallelism) | No (Concurrency only, single-threaded) |

| Switching | Pre-emptive (OS decides) | Pre-emptive (OS decides) | Cooperative (await yields control) |

| Key Challenge | Race conditions, deadlocks | IPC, serialization, memory overhead | ”Coloring” your code (async/await everywhere) |